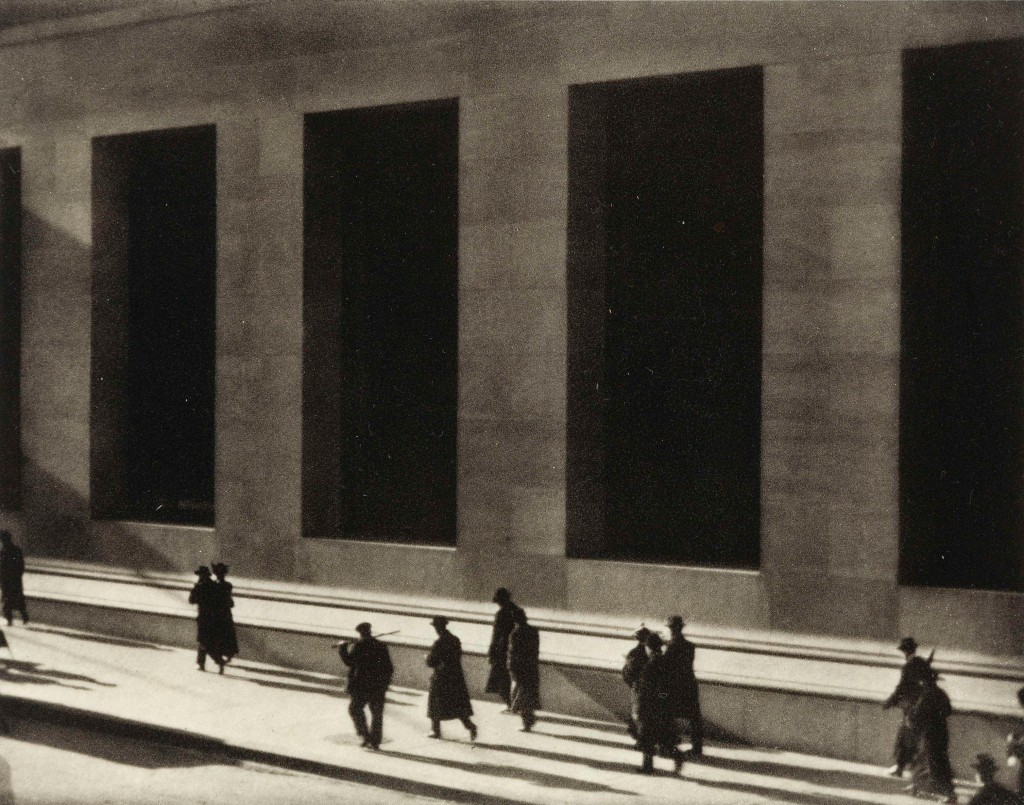

“Paul Strand’s 1915 photograph of Wall Street workers passing in front of the monolithic Morgan Trust Company can be seen as the quintessential representation of the uneasy relationship between early twentieth-century Americans and their new cities.” (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1995:230).

Wall Street, 1915 is indeed a picture full of tension, simultaneously celebrating the accomplishments of the modern world while fearing what they might imply.

The photograph was one of six Strand images published by Alfred Stieglitz in Camera Work (Strand and Barberie, 2014:14) that launched his career as an artist and marked a departure from his earliest work in the Pictorialist style (Jeffrey, 2008:114). Leaving behind “his faltering attempts at fogbound, neo-romantic landscapes in the nineteen-tens” (Dickson, 2016), Strand embraced Modernism in scenes from urban life and experiments with abstraction, perhaps influenced by Cubism (Koetzle, H.-M., 2002:170). The influence of the picture was significant and it has been credited with doing “much to lead American photography toward sharp-focus realism as well as abstraction, toward urban subjects and the machine aesthetic” (Milton W. Brown, cited in Wall Street, New York, 1915, s.d.).

More than a century later Wall Street, 1915 can easily be recognised as portraying a daily commute, with people walking to or from their place of work while the sun is low in the early morning sky. It depicts an urban scene, with background architecture that is both modern and clearly American rather than European. The building that serves as a backdrop for the commuters appears very institutional and suggests the intimidating power of a bank, major corporation, or government.

The frame is heavy with geometry and leading lines—a deceptively simple image containing little or no detail in the shadows. The print is somewhat muddy, with deep shades of black but no true whites. This may have been a conscious choice on the part of the photographer, given that the highly-directional side lighting should have been capable of producing both deep shadows and brilliant highlights.

The figures in the scene are all walking in the same direction and there is a palpable sense of deliberate slowness. One man—few of the walkers appear to be female—has shouldered a cane or walking stick at an angle contrary to all the others in the frame, a lone working-class punctum whose presence among the better-dressed walkers might prick the attention of the careful viewer (see Barthes, 2010:27). The commuters are pacing themselves, perhaps in no particular rush to begin the work day.

If the commuters are in no hurry, the solid stone mass of the building behind them appears positively immovable. Where there should be windows, deep, shadowed rectangles suggest unseeing eyes or open graves—Strand himself later spoke of its “sinister windows—blind shapes” (Jeffrey, 2008:115). The imposing geometry of the structure dominates the street scene, its scale a display of power that dwarfs the organic shapes moving in front of it.

Oblivious to the dark heaviness beside and above them, the people walk casually into a rising sun with its early light full in their faces. The dawn connotes the promise of a new day and perhaps carries with it additional promises of knowledge and hope for the future. The glare in their eyes might not allow them a view of where they are going, but they may follow the orderly lines laid out for them on the pavement. The walkers can probably not see each other very well and, even though some travel in small clusters, this is largely a collection of individuals. They move in a common direction but they are not together.

The people are the only non-geometric, organic shapes, but they too are given a kind of geometry by their own shadows that distinguish them from the vertical lines of the monolith behind, long arms pointing backward and slowing their progress.

Wall Street, 1915 has all the dramatic feel of a movie set, looking much like a production still from a silent film backlot. The same idea may have occurred to Strand himself because, although he later claimed that he did not know how he had made the picture (Strand and Barberie, 2014:14), he returned to the location and reproduced a close facsimile of the scene in the 1921 film Manhatta (1921). Just a few years later director Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) would offer a full-blown dystopian story of the evils of modern, mechanized city life, with great attention to the scale of buildings versus human figures—humans dominated by their own creations. Lang admitted that “the film was born from my first sight of the skyscrapers in New York in October 1924. […] I looked into the streets—the glaring lights and the tall buildings—and there I conceived Metropolis” (Minden and Bachmann, cited in Metropolis (1927 film) 2020).

But Wall Street, 1915 is not quite a dystopia. It is something more complex, managing to show “Strand’s willingness to accommodate documentary realism and abstraction within the same frame” (Paul Strand Artworks & Famous Photography, s.d.) and it is this tension that continues to give the photograph its power. The picture portrays an everyday scene of commuters heading to their place of work in an orderly, unhurried way leaving little trace of motion blur on the photographic plate. The walkers wear clothing that might be suitable for a cool spring or fall day, but they will enjoy a few moments to soak in whatever warmth may be had from the strong morning light.

If the reality conveyed by the image is common and reassuring, however, the abstraction is less so. The scene is crossed with graphic, sharp diagonals and inky rectangular pits that stay in the mind’s eye after the viewer has turned away—the kind of scene that Barthes might call subversive, “not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks” (Barthes, 2010: 38). The daily commute is played out against a menacing backdrop that hints physically and visually at the power the rising city and its economy have over the workers. It would not be too many more years before the same dark windows were witness to the explosion of an anarchist bomb (1920) and the stock market crash (1929) that would ruin so many hopes.

Strand’s workers stroll forever, enjoying the benefits of living in the great city. If they are aware of any tension, their pace does not show it. But the signs are there.

References

Barthes, R. (2010) Camera Lucida: reflections on photography. (Paperback ed.) New York: Hill and Wang.

Dickson, A. (2016) ‘Paul Strand’s Sense of Things’ 15/04/2016 At: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/paul-strands-sense-of-things (Accessed 07/12/2019).

Hambourg, M. M. and Strand, P. (1998) Paul Strand, circa 1916. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art : Distributed by H.N. Abrams.

Jeffrey, I. (2008) How to read a photograph: lessons from master photographers. New York: Abrams.

Koetzle, H.-M. (2002) Photo icons: the story behind the pictures. Köln; London: Taschen.

Manhatta (1921) – Documentary Film by Paul Strand (s.d.) At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qduvk4zu_hs (Accessed 11/01/2020).

Metropolis (1927 film) (2020) In: Wikipedia. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Metropolis_(1927_film)&oldid=935508307 (Accessed 12/01/2020).

Mißelbeck, R. and Museum Ludwig (Köln) (2005) 20th century photography: Museum Ludwig Cologne. Köln [etc.: Taschen.

MoMA | Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler. Manhatta. 1921 (s.d.) At: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/paul-strand-charles-sheeler-manhatta-1921/ (Accessed 05/01/2020).

Paul Strand (s.d.) At: http://iphf.org/inductees/paul-strand/ (Accessed 07/12/2019).

Paul Strand | artnet (s.d.) At: http://www.artnet.com/artists/paul-strand/ (Accessed 07/12/2019).

Paul Strand Artworks & Famous Photography (s.d.) At: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/strand-paul/ (Accessed 05/01/2020).

Philadelphia Museum of Art (1997) Handbook of the collections. Philadelphia, Pa.: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Philadelphia Museum of Art – Collections Object : Wall Street, New York (s.d.) At: https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/73744.html (Accessed 05/01/2020).

Selwyn-Holmes, A. (2010) Wall Street by Paul Strand. At: https://iconicphotos.wordpress.com/2010/12/13/wall-street-by-paul-strand/ (Accessed 05/01/2020).

Stieglitz, A. and Philippi, S. (2008) Camera Work: the complete photographs 1903 – 1917. Hong Kong: Taschen.

Strand, P. and Barberie, P. (2014) Paul Strand. (Second edition) New York, N.Y: Aperture.

Wall Street, New York, 1915 (s.d.) At: https://aperture.org/shop/paul-strand-wall-street-new-york-1915-photograph (Accessed 05/01/2020).