Jeff Wall (Vancouver, 1946– )

- MA art history from UBC, 1970. Postgraduate research at the Courtauld Institute in London from 1970–73.

- Draws on elements from other art forms—including painting, cinema, and literature—in an approach he calls “cinematography.” Large scale constructions and montages. Conceptualism.

- Frequently displays work as backlit color transparencies, similar to street advertising, but has more recently worked with b/w printing and inkjet colour.

- Early work sometimes evoked other artworks: “The Destroyed Room (1978) explores themes of violence and eroticism inspired by Eugène Delacroix’s monumental painting The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), while Picture for Women (1979) recalls Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) and brings the implications of that famous painting into the context of the cultural politics of the late 1970s.”

- “Near documentary” work made in collaboration with non-professional models who appear in them.

Jeff Wall (2018) At: https://gagosian.com/artists/jeff-wall/ (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Jeff Wall (2020) In: Wikipedia. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jeff_Wall&oldid=934463406 (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Jeff Wall Photography, Bio, Ideas (s.d.) At: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/wall-jeff/ (Accessed 26/01/2020). Tate (s.d.)

Jeff Wall: room guide, room 6. At: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/jeff-wall/jeff-wall-room-guide/jeff-wall-room-guide-room-6 (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Lubow, A. (2007) ‘The Luminist’ In: The New York Times 25/02/2007 At: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/25/magazine/25Wall.t.html (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Hannah Starkey (Belfast, 1971– )

- Studied photography and film at Napier University, Edinburgh (1992–1995) and photography at the Royal College of Art, London (1996–1997). Lives and works in London.

- Works predominantly with women as subjects, actresses as well as people she meets on-site to develop scenes. Stark architecture and strong colour.

- Says of her photographs that they are “explorations of everyday experiences and observations of inner city life from a female perspective.”

- Works are frequently untitled and show freeze-framed crisis points: issues of class, race, gender, and identity. Intimate moments.

Hannah Starkey | artnet (s.d.) At: http://www.artnet.com/artists/hannah-starkey/ (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Hannah Starkey – Artists – Tanya Bonakdar Gallery (s.d.) At: http://www.tanyabonakdargallery.com/artists/hannah-starkey/series-photography_4 (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Hannah Starkey – Artist’s Profile – The Saatchi Gallery (s.d.) At: https://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/hannah_starkey.htm (Accessed 26/01/2020).

O’Hagan, S. (2018) ‘The photography of Hannah Starkey – in pictures’ In: The Guardian 08/12/2018 At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2018/dec/08/the-photography-of-hannah-starkey-in-pictures (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Tom Hunter (Bournemouth, 1965– )

- Works in photography and film. Photographs often reference and reimagine classical paintings. First photographer to have a one-man show at the National Gallery, London.

- Socially- and politically-motivated work.

- “Painters inspire me most – Caravaggio, Vermeer – but I also like Dorothea Lange and Sally Mann.”

- Series “Persons Unknown”: portraits of squatters in the abandoned Hackney warehouses. Won the Photographic Portrait Award at the National Portrait Gallery in 1998 for an image of a young woman with a baby beside her, reading a possession order, shot like a Vermeer painting.

Pulver, A. (2009) ‘Photographer Tom Hunter’s best shot’ In: The Guardian 04/11/2009 At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/nov/04/photography-tom-hunter-best-shot (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Tom Hunter – Artist (s.d.) At: http://www.tomhunter.org/ (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Tom Hunter – 29 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy (s.d.) At: https://www.artsy.net/artist/tom-hunter (Accessed 26/01/2020). Tom Hunter – Artists – Yancey Richardson (s.d.) At: http://www.yanceyrichardson.com/artists/tom-hunter (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Tom Hunter – Artist’s Profile – The Saatchi Gallery (s.d.) At: https://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/tom_hunter.htm (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Unheralded Stories Series | Tom Hunter (s.d.) At: http://www.tomhunter.org/unheralded-stories-series/ (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Taryn Simon (NYC, 1975– )

- Multidisciplinary artist in photography, text, sculpture, and performance. Work featured in the Venice Biennale (2015). Guggenheim Fellow, 2001.

- Studied environmental sciences at Brown University but transferred to a degree in art-semiotics, while taking photography classes at Rhode Island School of Design. BA 1997. Visiting artist at Yale, Bard, Columbia, School of Visual Arts, and Parsons School of Design.

- The Innocents (2003) — stories of individuals wrongly sentenced to death or life, then released and gained exoneration due to DNA evidence. Mistaken identity, questionable reliability of evidence.

- An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (2007) — objects, sites, and spaces integral to America but not accessible to public (radioactive capsules at a nuclear waste storage facility; black bear hibernating; CIA art collection).

- Heavy research and preparation for each project: “The majority of my work is about preparation. The act of taking photographs is actually a very small part of the process. I work with a small team, just my sister and one assistant.”

O’Hagan, S. (2011) ‘Taryn Simon: the woman in the picture’ In: The Observer 21/05/2011 At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/may/22/taryn-simon-tate-modern-interview (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Taryn Simon (s.d.) At: http://www.tarynsimon.com/ (Accessed 26/01/2020a).

Taryn Simon (s.d.) At: https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/taryn-simon (Accessed 26/01/2020b).

Taryn Simon – 107 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy (s.d.) At: https://www.artsy.net/artist/taryn-simon (Accessed 26/01/2020).

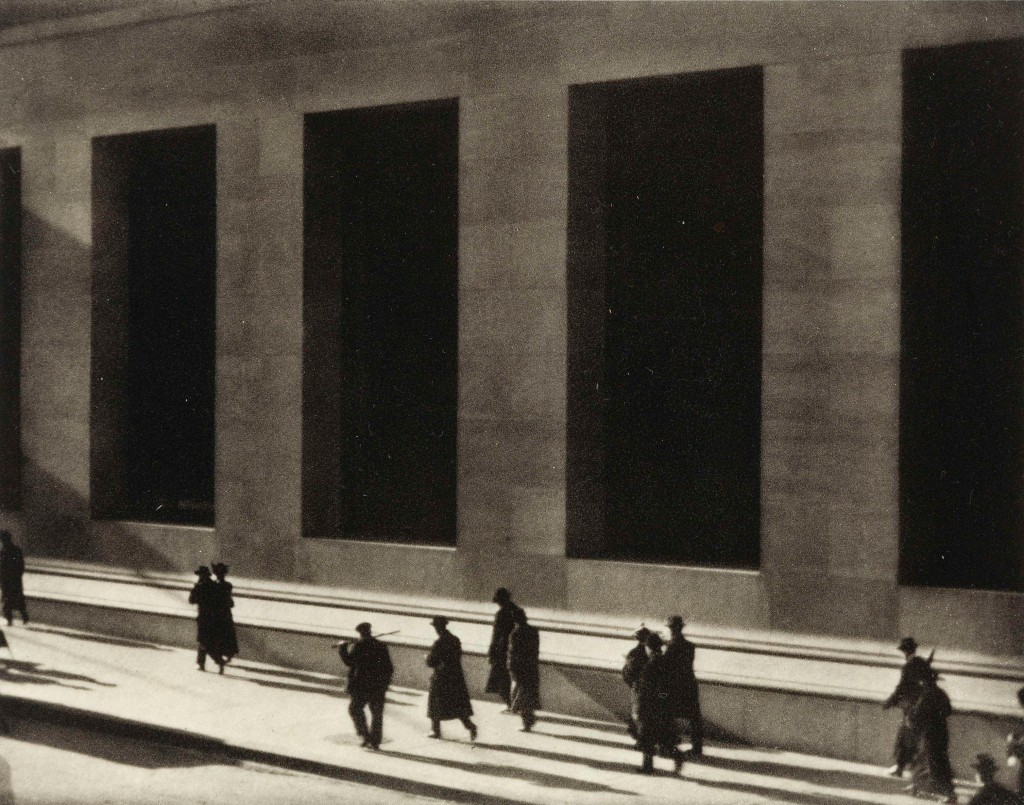

Philip-Lorca DiCorcia (Hartford, 1951– )

- Studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Then attended Yale, MFA Photography, 1979. Lives and works in NYC and teaches at Yale.

- Mixes snapshots and staged compositions that are theatrical in nature. Carefully planned staging, documentary, cinema and advertising. Line between reality and artifice/fantasy blurred.

- Accidental poses, unintended movements, insignificant facial expressions. Series, Hustlers, Streetwork, Heads, A Storybook Life, and Lucky Thirteen, conceptual in nature.

DiCorcia, P.-L. (2001) Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Heads. Steidl Box Pacemacgill.

Kimmelman, M. (2001) Philip-Lorca diCorcia — ‘Heads’. At: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/14/arts/art-in-review-philip-lorca-dicorcia-heads.html

MoMA Learning. At: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/philip-lorca-dicorcia-head-10-2002

Philip-Lorca diCorcia | MoMA. At: https://www.moma.org/artists/7027

Philip-Lorca diCorcia | artnet (s.d.) At: http://www.artnet.com/artists/philip-lorca-dicorcia/ (Accessed 26/01/2020).

Philip-Lorca diCorcia – 46 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy (s.d.) At: https://www.artsy.net/artist/philip-lorca-dicorcia (Accessed 26/01/2020).